Last week, I finished the newest work by David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Emancipation, considered the final volume in his trilogy about the history of slavery. While the entire work was interesting, from his discussion about the complicated process of abolishing slavery, to the colonization movement in the United States, and the status of free blacks as a window into how slaves were viewed, his thoughts on the larger question of moral progress and human history in the conclusion were most interesting to me. While it is hard, he writes, to look at the blood-soaked history of the 20th Century and imagine that we are making moral progress, the abolition of chattel slavery in the West stands as a shining example of this very idea, that within roughly two hundred years we ended a practice that had been accepted for thousands of years. The question of race in the United States is, however, another matter entirely.

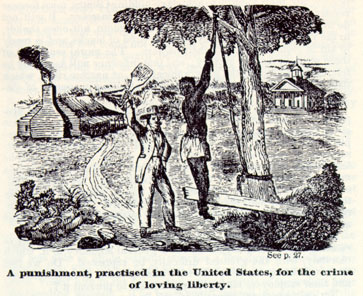

Davis begins with a discussion about the animalization of humans required by chattel slavery. It is a process of seeing fellow human beings as somehow less than human--at best, humans who are like children in need of guidance. This idea reoccurs throughout the book. Newly-enslaved Africans were viewed as lazy without the lash to drive them, as stupid and occasionally vicious without the harsh measures of slavery to keep them in line. Slavery apologists pointed to the aftermath of the Haiti revolt as evidence of both these ideas, exaggerating and fabricating stories of the most grotesque cruelties imaginable done by former slaves. The desire of freed slaves in Haiti to cease working in highly-profitable plantations, and instead to work small subsistence plots for their own food, was highlighted as evidence of their innate desire to be idle.

Free blacks in the North, with notable exceptions like Frederick Douglass, were relegated to the lowest ranks of society, deliberately kept from truly being free. Denied the vote by law, after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act they could be reenslaved at any moment. Barred from joining existing institutions, they often chose to form their own. Slavery itself persisted in the North far longer than many realize; while most Northern states began to abolish slavery in the late 18th and early 19th Centuries, this often took the form of gradual emancipation, a process that could span decades, ensuring that men and women would remain in bondage for many years longer.

All of this is not ancient history, some irrelevance that can be trotted out as interesting bits of trivia. The legacy of slavery and how it shaped the United States is still with us. The questions of race that we continue to deal with today are a direct result of this history. It is only by understanding our history, by refusing to turn away from the shameful practice of slavery in the United States and its legacies, that we can hope to tackle issues of race in an honest way. Yet how can we do this when presentations of U.S. history in high school, in many cases the only exposure citizens will get to this history, are often so painfully bad?

Reading Davis' work is a reminder that what is presented in high school history classes is so far removed from the real history of slavery in the United States as to render the former a caricature, oversimplified to the point of being wrong. When slavery is presented as a side issue rather than the central question of U.S. history, when we gloss over the tragedy of Reconstruction's failure, brought down by racist backlash at attempts to enshrine black equality into practice as well as law, how can we expect those who were taught this bowdlerized history to deal with the complexities of these twin legacies? Do we really think that allowing students to be taught that "states' rights", not slavery, was the cause of the Civil War is going to lead to citizens who will be able to participate meaningfully in discussions of race and equality, or even understand that there is something worth discussing?

For me, the process of understanding why race remains an issue, and recognizing my own white privilege, grew out of a more detailed study of slavery and its aftermath. It's hard to pretend that our society treats everyone equally when reading history tells us that's just not so, that we have a history of treating everyone quite unequally, in spite of our rhetoric to the contrary. If we are to move forward in achieving true equality, we cannot imagine that we will do so without an honest accounting of our history.

Comments

Post a Comment