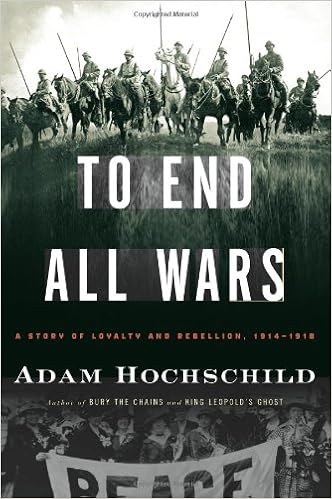

A few weeks ago, I was stuck in the airport, my flight delayed by five hours. While I tend not to read many ebooks myself, on that Friday, however, I was very glad to have remote access to my library's online collection to ease the boredom of the wait and the subsequent flight. Adam Hochschild's To End All Wars was a book that I had meant to read a while ago but never gotten around to, and it proved an engrossing read.

Just over a century ago when the nations of Europe declared war on one another, much of the populace broke out into spontaneous celebration. Cheering crowds gathered before the royal palaces in Germany, Russia, and Britain. It was a war that many in Europe had expected for years, war's outbreak an event that had been both feared and longed for. But not everyone was cheering, and it is the dissenters to the war that Hochschild focuses much of his attention on. While men like Rudyard Kipling celebrated the war as heroic, others like Bertrand Russell spoke out against what seemed to them an utterly senseless conflict. While patriotic fervor swept up many, some socialist leaders called upon workers of all nations to refuse to fire on each other. Reformers like Charlotte Despard, who had already been jailed for her work on behalf of women's suffrage, opposed conscription; conscientious objectors went to prison, and some were executed at the front for refusing to fight.

The longer the war went out, with casualties at major battles in the tens of thousands with little gain to speak of and food growing short on the homefront, the more opposition to the war grew. While David Lloyd George and the commanders of the British military made plans for a war that they expected would stretch on until at least 1920, the number of deserters on all sides increased. After the first pangs of the Russian Revolution ousted the Tsar, the Provisional Government under Alexander Kerensky pledged, under pressure from the Western Allies, to fight on. After years of suffering under a succession of inept commanders, however, many Russian soldiers had other ideas. Often murdering their officers, they abandoned the front by the thousands. Tired of being sent to a pointless death by indifferent commanders like Douglas Haig, the British army nearly revolted in 1918. German naval units, ordered to sail out in a glorious, but useless, final battle at wars' end, had had enough too. They mutinied, and revolt by socialist and communist forces across Germany sent the Kaiser fleeing into exile. As Hochschild recounts in this masterful work, the dissent of a brave few at the war's beginning had become the revolt of many at war's end. Too many had died for too little. Too many had died for nothing at all.

The First World War, with its millions dead and millions more wounded, isn't just a clearly pointless conflict to us now. Many at the time it happened could see how senseless it was too, without the virtue of hindsight that we possess now. Those few, courageous voices spoke up even as the governments of the time sought to silence them, through prison, through finding and destroying printing presses, and through attacking and demeaning them with merciless propaganda, calling them cowards and questioning their patriotism. For all the attacks that were levied against the dissenters of the Great War they were, in the end, right. Hochschild's gift is in bringing forward these voices again, as a reminder and caution to us now, deftly weaving the stories of these individuals with the progression, in all its tragedy, of the war itself. To End All Wars is the story of courage, of honor, in a time when it seemed that all of the world had gone mad. As we mark the ongoing centenary of the First World War, it is these voices speaking out against an unfolding tragedy that we need to remember now, far more than some glorified, sanitized version of war, more than any jingoistic narrative that would seek to justify the conflict. For all the progress we have made since then, we remain far too susceptible to the same madness that descended upon Europe in 1914.

The longer the war went out, with casualties at major battles in the tens of thousands with little gain to speak of and food growing short on the homefront, the more opposition to the war grew. While David Lloyd George and the commanders of the British military made plans for a war that they expected would stretch on until at least 1920, the number of deserters on all sides increased. After the first pangs of the Russian Revolution ousted the Tsar, the Provisional Government under Alexander Kerensky pledged, under pressure from the Western Allies, to fight on. After years of suffering under a succession of inept commanders, however, many Russian soldiers had other ideas. Often murdering their officers, they abandoned the front by the thousands. Tired of being sent to a pointless death by indifferent commanders like Douglas Haig, the British army nearly revolted in 1918. German naval units, ordered to sail out in a glorious, but useless, final battle at wars' end, had had enough too. They mutinied, and revolt by socialist and communist forces across Germany sent the Kaiser fleeing into exile. As Hochschild recounts in this masterful work, the dissent of a brave few at the war's beginning had become the revolt of many at war's end. Too many had died for too little. Too many had died for nothing at all.

The First World War, with its millions dead and millions more wounded, isn't just a clearly pointless conflict to us now. Many at the time it happened could see how senseless it was too, without the virtue of hindsight that we possess now. Those few, courageous voices spoke up even as the governments of the time sought to silence them, through prison, through finding and destroying printing presses, and through attacking and demeaning them with merciless propaganda, calling them cowards and questioning their patriotism. For all the attacks that were levied against the dissenters of the Great War they were, in the end, right. Hochschild's gift is in bringing forward these voices again, as a reminder and caution to us now, deftly weaving the stories of these individuals with the progression, in all its tragedy, of the war itself. To End All Wars is the story of courage, of honor, in a time when it seemed that all of the world had gone mad. As we mark the ongoing centenary of the First World War, it is these voices speaking out against an unfolding tragedy that we need to remember now, far more than some glorified, sanitized version of war, more than any jingoistic narrative that would seek to justify the conflict. For all the progress we have made since then, we remain far too susceptible to the same madness that descended upon Europe in 1914.

Comments

Post a Comment